Most people who have followed popular music for any length of time are familiar with the concept of a “single.” If you are not familiar, a single is a track released for wide distribution on the radio. The single may be part of a full-length album, and if it is, it has been identified as the catchiest song most likely to make a lot of money. It therefore gets quite a bit of exposure by finding it’s way onto “Best of Lists.”

Many music listeners have approached music with only the singles in mind. A smaller fraction of listeners penetrate the “deep cuts” buried within the back half of any particular album. Thus many of even the greatest bands have songs that their fans have never heard before. These tracks are relegated to cult favorite status and perhaps even forgotten unless you stumble upon it after falling into a Youtube wormhole. One fine example of this phenomenon is Led Zeppelin. It’s hard to imagine a person who isn’t familiar with tracks like “Stairway to Heaven” or “Kashmir,” but only the diligent, patient fan is able to sink his or her teeth into a song like “Carouselambra.”

So it is with hiking as I’ve observed from monitoring the habits of other hikers on social media. Every day, I see mention of the “Kashmirs” and “Stairways” of the natural world in the form of Mt. Baldy or Runyon Canyon or Torrey Pines. Everybody knows them, and everybody seeks them out. Somewhat less often but still frequently, you see the “Rock and Roll’s,” “Over the Hills and Far Away’s,” and the “Fool in the Rain’s,” in the form of Echo Mountain, Woodson Mountain, or Sturtevant Falls. But it’s not often that you hear somebody bragging about sitting through “Carouselambra.” It’s a weird song, filled with unexpected twists and turns, not terribly accessible, and probably longer than it ought to be.

If Southern California is the Led Zeppelin of hiking with a deep, rich, and astonishingly varied catalog, the Sawmill Trail to Santa Rosa Mountain is its “Carouselambra.” This “deep cut” goes to all kinds of unexpected places, contains a lot of weird stuff, goes on for longer than you’d think, and like Jimmy Page’s guitars swallowed by too much heroin, the trail you’re expecting is often a little hard to follow. For the connoisseurs of remote and obscure places, this odd mixture of experiences is worth seeking out.

This ambitious, rambling, even disjointed hike serves up a forgotten slice of California history, magnificent views of SoCal’s two most beautiful desert valleys, backpacking with actual permanent water sources, multiple traces left by long-gone desert eccentrics, and the sort of workout you’d pay your personal trainer a lot of money for. If that hits all of the right notes for you, please proceed.

The Sawmill Trail shares a trailhead with the adjacent Cactus Spring Trail, but unlike Cactus Spring, the Sawmill Trail wastes no time in beginning to climb. It doesn’t stop climbing until you finally reach the Santa Rosa Crest some 8.7 miles into the hike. The first 5.9 miles of the Sawmill Trail follow a sometimes bumpy dirt road leading to the eponymous sawmill and which now serves as a multi-purpose route attracting mountain bikers, hikers, and off-road enthusiasts. The road switchbacks up the northern flank of Santa Rosa Mountain at a moderate grade while gradually transitioning through high desert flora and then montane chaparral before finally penetrating the conifer belt just before the end of the road. Along the way, you will enjoy plenty of views encompassing the Coachella Valley and the San Jacinto Mountains, which all improve as you progress.

The end of the road is also where the hike really gets interesting. At the end of the road, you will find a 15-foot charcoal kiln that was once a part of a sawmill that sought to exploit Santa Rosa Mountain’s once abundant timber. Lumbermen in the area sought out the timber for use in constructing the Inland Empire in much the same way that Bay Area lumbermen sought out Redwood and Douglas fir to build up San Francisco. Unfortunately, Southern California’s semi-arid climate does not support rapid coniferous regeneration the way that Northern California’s cooler, wetter climate does, and so the lumbermen depleted the timber at an unsustainable rate. There’s still a good amount of remaining timber, especially when you step into the Santa Rosa Wilderness, but astute and inquisitive hikers will find stumps of formerly grand Jeffrey pines and incense cedars.

Adjacent to the kiln, you will also be able to find a spring-fed pond that had dried up because somebody has diverted the spring. Plenty of flat areas abound to pitch a tent, and the views alone make this an outstanding place to camp. The nearby spring runs year-round, providing your most reliable source of water until you get to the top of the Santa Rosa Crest.

The continuation of the route follows a vague and poorly marked trail that leads away from the pond. The degraded dirt road through which the spring runs will lead you to some rusted old logging equipment. Satellite images show that the road, which isn’t charted on maps, will actually reach the Santa Rosa Crest near Toro Camp, thus creating a potential for a looping route. However, I did not scout this section and can’t verify whether it’s passable or safe.

The San Jacinto Mountains

Once you find the narrow, faint path leading from the pond, you will quickly cross over into the wilderness and its wilder terrain. Chaparral makes a brief comeback as the trail passes through some overgrown sections marked by more remnants of the old logging camp before returning to the trees. At 6.7 miles, keep left at a faint junction marked by a Forest Service (5E03) sign to continue climbing toward the dense timber now directly ahead of you. As the trail penetrates the forest, it becomes occasionally vague and occasionally easy to follow with sporadic blow downs presenting minor obstacles. Attentive hikers shouldn’t have much trouble following the path, but anybody letting their mind wander may miss a few vague switchbacks and go off course.

After dipping into a rocky ravine shaded by towering conifers at 7.1 miles, the trail continues climbing obliquely toward the Santa Rosa crest. At various points, gaps in the trees allow glimpses at the ever-more-impressive views, allowing you to marvel at the remote, secluded forest world you reached from the higher parts of the desert. Dense forest occasionally gives way to sunnier patches of thinner forest and shrubs on south-facing slopes, but for the most part you remain in forest every bit as dense and magnificent as the forests of the San Jacinto Mountains while you climb.

After switchbacking through a broad ravine for what feels like an inordinately long time, you finally top out at Santa Rosa Mountain Road, which runs along the crest of the range from Highway 74 to the base of Toro Peak. Sure, you could drive up here as many people do to take advantage of the free yellow post campsites scattered along the road, but then you would have missed everything over the last 8.8 miles. Those same campsites might serve well as backpacking sites. Even though they don’t have the remote wilderness feel associated with backpacking, they are still far enough from civilization to scratch the seclusion itch for most hikers. Santa Rosa Spring, which lies south (right) along the road will provide a place to tank up.

Note that the road is probably as far as most dayhikers are going to be able to go. The really extreme folks won’t have trouble getting to the summit, but nearly everybody will enjoy summitting the mountain more if you do it over two days.

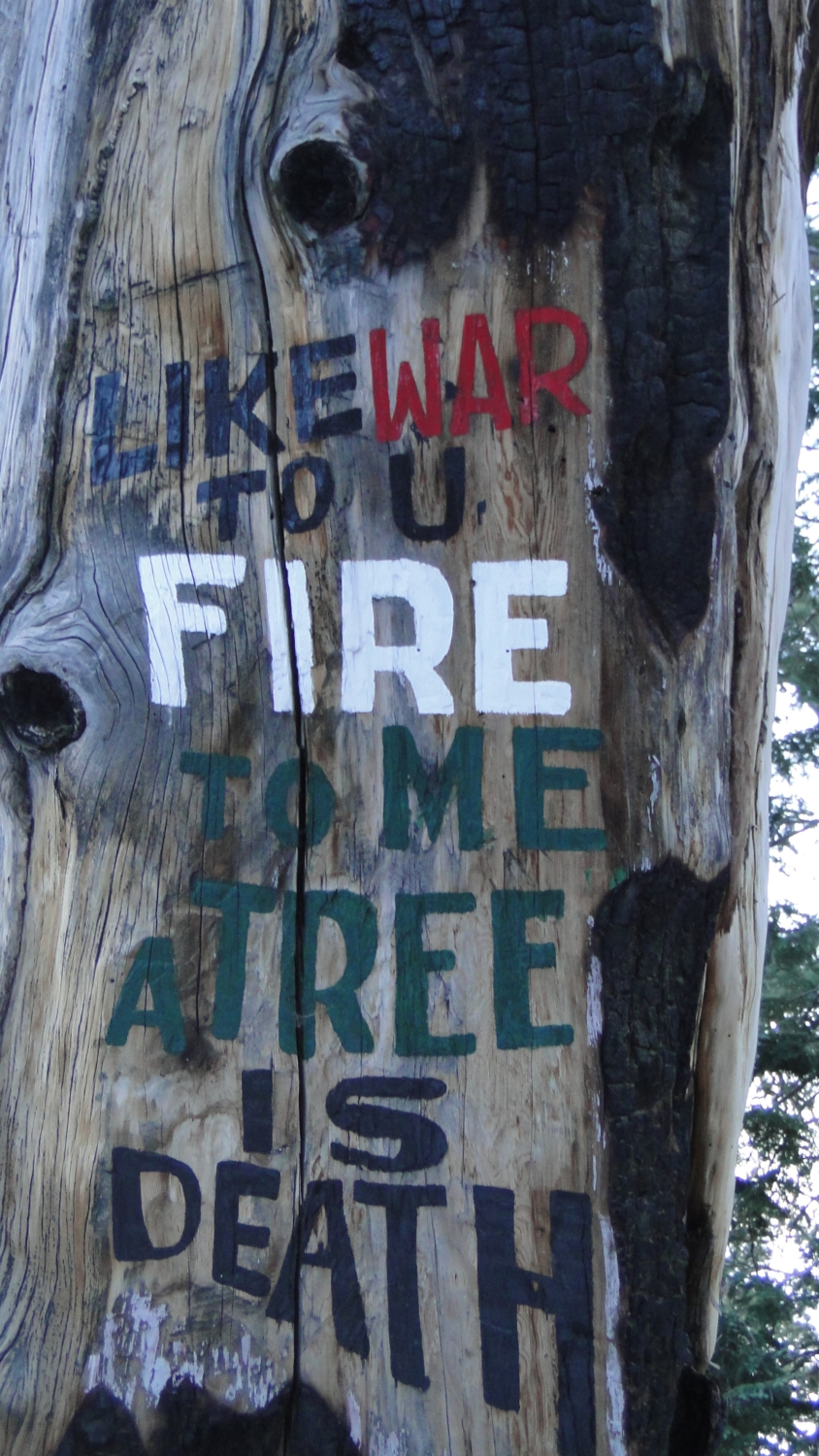

From the junction with the Sawmill Trail and Santa Rosa Mountain Road, turn left and begin heading east along the north face of Santa Rosa Mountain. The wide, smooth grade of the road presents a dramatic change from the narrow single track you were following earlier, but the forest becomes more impressive the further you go. You also have a chance to enjoy some of the bad poetry left behind by Desert Steve Ragsdale, the former desert entrepreneur who opened a way station along what is now I-10 before his extra-marital dalliances earned this ostensibly pious tea-totaler an exile to a cabin on the summit of Santa Rosa Mountain. His poetry painted onto rocks and burnt out pine snags warns of fire and its damage to the forest. You may roll your eyes and nod in admiration, perhaps at the same time while you walk pass. If the verbiage is too clunky for your enjoyment, fix your gaze on the view and forget about the musings of Desert Steve.

Borrego Valley

At 9.7 miles, an access road leading to the summit splits away on the right. Follow this road as it meanders past several fine campsites before arriving at the summit marked by the remains of Ragsdale’s cabin. The cabin burnt down leaving only the chimney and fire pit behind. In addition to the campsites, here on the summit you will enjoy the finest views in every direction except southeast toward the obstacle of Toro Peak. Borrego Valley and the entirety of Anza-Borrego Desert Park unfurls to the south, while the rest of the mountains of the Inland Empire – the San Gabriels, Santa Anas, San Bernardinos, Palomars, and San Jacintos tower above hazy flatlands. Conifers contrast against vast desert spaces, showcasing the wonders of Southern California in one expansive vista.

Tags: Borrego Valley, Coachella Valley, San Bernadino National Forest, San Jacinto and Santa Rosa Mountains National Monument, Santa Rosa Mountains, Santa Rosa Wilderness, Sawmill Trail, Toro Peak