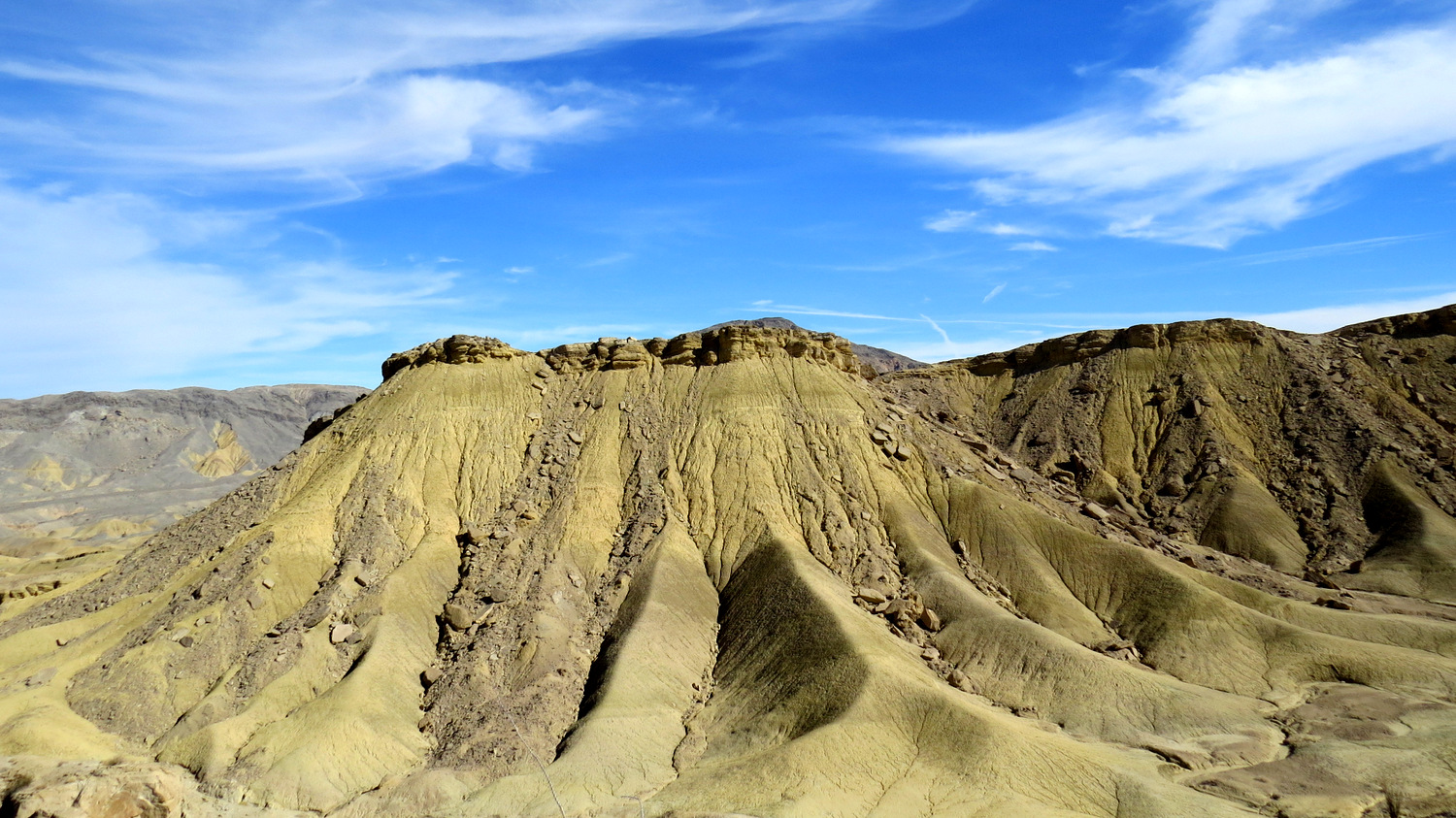

This marvelous wilderness area features some of the most fascinating geology anywhere in Southern California. On this moderately strenuous desert odyssey, hikers will encounter abundant fossils, sandstone formations with caves gouged out by the howling desert winds, narrow canyons with a bewildering combination of rock types, a maze of mud hills, and impressive views across Anza-Borrego Desert State Park’s Carrizo Badlands.

Over millions of years, the waters of the nearby Gulf of California waxed and waned in accordance with larger climactic cycles. When global temperatures warmed, the Sea of Cortez would flow into the Salton Sink, covering the landscape with a warm, shallow sea. When the temperatures cooled, the seas would recede, leaving behind layers of sediment. Each layer of sediment was unique in composition; sometimes, the sediment was composed of coarse sand particles. Other times, the sediment was a finer, siltier material left behind during times when the Colorado River’s flow shifted and formed a delta. The tropical inland seas also harbored a wide array of marine life, ranging from large snails called gastropods to walruses.

As the endless cycles of marine succession and recession progressed, a geological layer cake composed of numerous layers of rock often embedded with marine fossils formed across the region. As this region also lies along one of the largest and most active faults in North America (the San Andreas), this layer cake has been twisted, contorted, smashed, bashed, and crumpled over the eons, bringing many of the different layers to the surface and exposing fossils in certain places. Rainfall, often in the form of violent flash flooding, carved the landscape into fantastic formations creating a bewildering maze of canyons.

As you explore the Domelands area, you travel through a combination of ancient sea beds and the contents the Grand Canyon carried hundreds of miles via the Colorado River. All of it has been crystallized by time and pressure into the magnificent landscape protected by the Bureau of Land Management’s Coyote Mountain Wilderness.

Despite the timelessness of this landscape, hikers should know that it is exceptionally fragile. The Coyote Mountain Wilderness is a region of critical environmental concern, and all visitors should take pains to tread as lightly as possible. Those who do visit the Domelands will come away with one of the richest, most impressive geological experiences available in the Anza-Borrego Desert region. Just make sure you don’t also come away with fossils, which belong in the desert and must stay in the desert.

Finally, the informal paths referenced in this write-up are clear enough when you’re following them, but there are some navigational challenges on the route that may prove daunting or insurmountable to those without a map. You can rely on the GPS track, but it would still be wise to have a topographic map and compass, especially for some of the more poorly defined junctions on the route.

Beginning from the staging area, find the footpath that enters a series of yellow mud hills composed of fine silt deposited by various incarnations of the Colorado River Delta and the Sea of Cortez. This road will bend to the left and commence a climb through the mud hill area. At .9 mile, a wash flowing in from the right meets the trail. Turn right to follow the wash. Smoke trees dot the wash here and there, but otherwise, the landscape is raw, primeval, and utterly fascinating.

A wide path climbs out of the wash at 1.3 miles, continuing along on informal foot paths towards the base of a line of hills to the northeast. At the base of the hills, you’ll reach a junction with a trail climbing the hills through a ravine and another trail branching off on the right toward a deep crease in the Earth. The ravine trail will be your return route; turn right and head .2 mile toward the canyon to the south.

The path brings you to the canyon’s rim, from which you will continue to follow the path down into the canyon. Once at the canyon’s bottom, the yellow mud hills transition into beige sandstone with numerous outcrops of exotic metamorphic, granitic, and other sedimentary rocks exposed at various points. As you progress deeper into the canyon, keep your eyes peeled for fossils, which will appear in abundance.

3 miles in, the canyon deepens and narrows into a few twisting alleys and tight squeezes. Through these spots, you’ll encounter a number of different fossils, including gastropods, sand dollars, clams, and a variety of fragments. Remember that you must do your part not to negatively impact the landscape, which means not removing any of the fossils. Everything must remain exactly where and as you found it.

As you continue, look to the left for a deep cleft in the canyon wall. A 50-foot dry fall plunges from a narrow hanging canyon above. A delicate natural bridge spans the precipice of the fall. Don’t attempt to climb up the sheer walls here; this route will bring you down to the natural bridge from above later on in the hike.

The next navigational decision arrives when you reach a large sedimentary mesa composed of gray-ish mudstone directly to the east (your right). Climb the rock shelf on your left and commence a steep climb southwest along the rim of the canyon you’ve just been walking down. An informal path illuminates the way, but you should soon be able to see the honeycombed sandstone domes at the heart of this route ahead and to the right/west.

As you climb, you’ll cross a sinuous tributary snaking its way downhill to the canyon below. Turn left here and follow the tiny wash. As you progress, the walls grow higher until you suddenly find yourself face-to-face with the natural bridge you so recently stared up at from below. A depression below the arch indicates a spot where water has gouged a pool that fills up during flash floods. Return back up the wash to resume the hike.

After carefully picking your way up the edge of the canyon, turn right once you reach a ridge and begin traversing northwest toward the sandstone domes. Some of these domes contain caves that are large enough to hold several prone bodies; backpackers in the past have used them for sleeping. Other caves provide ideal spots for a nice lunch break.

The views from this high point are splendid; you’ll enjoy the rumpled, tortured landscape for miles around. The domes themselves invite hours of scrambling and exploration, so be sure to budget some time and energy to poke around.

When you’re ready to continue, proceed west along an informal path to a peak labeled “1662” on the topo. As you approach the peak, you’ll find yourself treading along a fossilized reef bed atop the mountain, which should provide an indication of just how much geologic action has occurred to rise this ancient seabed 1600 feet above sea level.

From the top of peak 1662, the views to the east and north reveal the broad expanse and corrugated landscape of the Carrizo Badlands, a massive plain dominated by the carved remnants of ancient sea beds that hide countless geologic wonders within their folds. This inspiring view is incredible at sunrise when shafts of winter light draw the color out of the various sedimentary layers across the badlands.

Proceed on the informal path as it begins to descend through a ravine and back toward the junction you encountered at mile 2. From here, retrace your steps back into the wash and then make a left turn to pass through the mud hills back to the trailhead.

Tags: BLM, Carrizo Badlands, Coyote Mountain Wilderness, Domelands, fossils, Imperial County, Mud Hills, wind caves