An easy nature trail outside a fascinating UNESCO World Heritage Site that provides a great opportunity to learn how the region’s First Nations people utilized this unique terrain over thousands of years. A wonderful accompaniment to the excellent on-site museum and a great place to experience the wide-open magic of Canada’s Great Plains.

Located between Calgary and Waterton Lakes National Park, the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump World Heritage Site is an incredible place with an incredible name to match. For more than 5,000 years, the Blackfoot tribes [in reality, three separate tribes — the Blackfoot (Siksika), Bloods (Kainai), and Peigan (Pekuni)] utilized the landscape at Head-Smashed-In and other similar locations to herd and hunt buffalo during the summer months. These hunts took a tremendous amount of skill, planning, and execution, and were also important social and cultural events for those who participated.

Today, visitors on the Plains can drop into the beautiful interpretive centre to learn more about this tradition. Previously a National Historic Site, Head-Smashed-In was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1981. The interpretive center began construction in 1984 and was officially opened three years later. It’s unique design effectively hides the building inside the landscape and the interior provides a beautiful opportunity for telling the region’s story.

On the inside, the centre’s exhibits bring the region’s story to life, teaching visitors about buffalo hunting culture, the introduction of European settlers to the region, and the unique archeological work that continues in the area to this day. We recommend exploring the visitor center and the short paved walk on the top of the cliff before hiking the lower trail, as it will give you a better understanding and appreciation of what you’re looking at.

the cliffs from the top. Skilled buffalo hunters directed charging herds off these cliffs, where other tribe members below butchered the animals for food and supplies

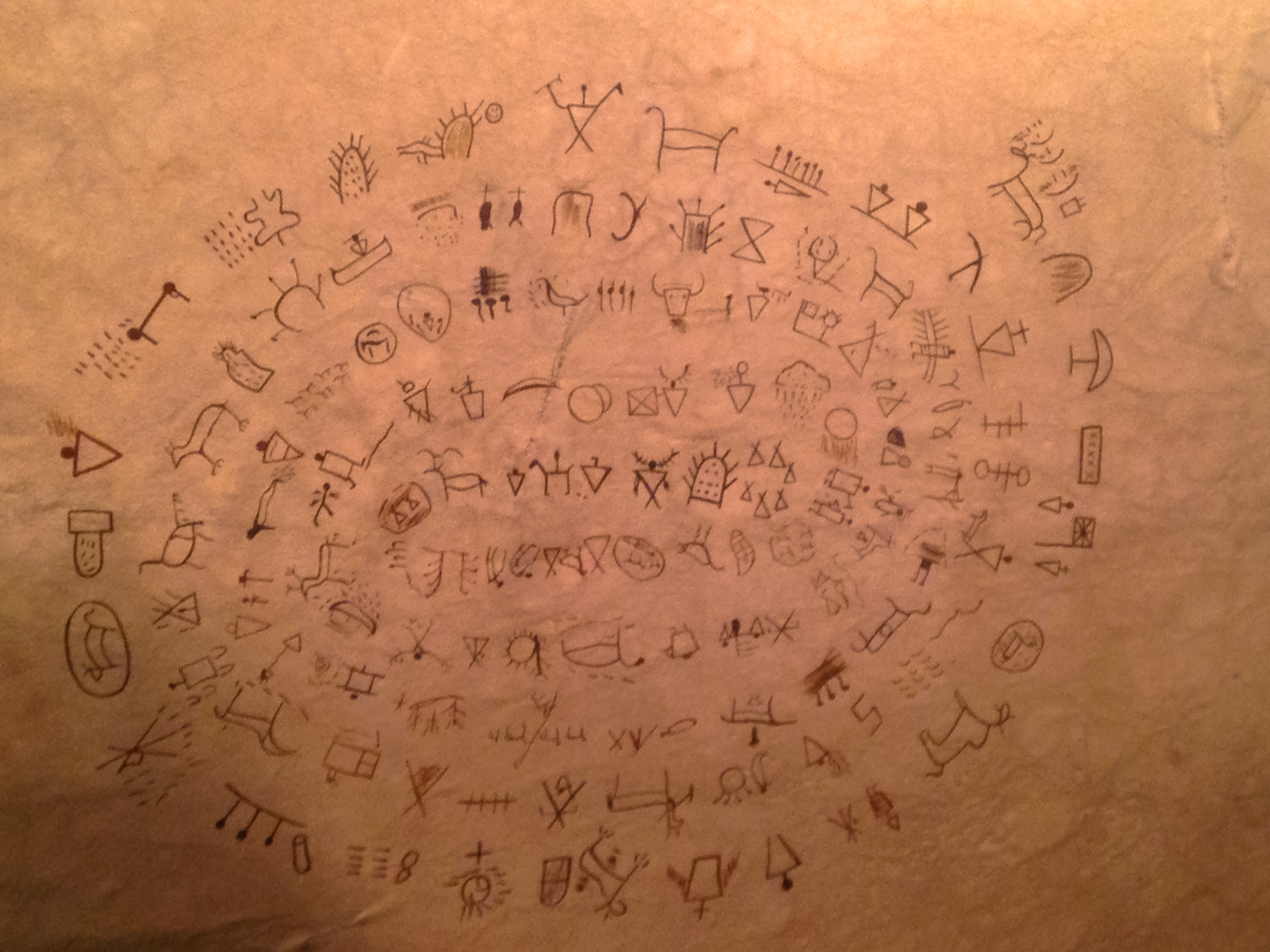

an etched leather hide detailing a single symbol representing each year of the buffalo hunt

When you’re done soaking in the exhibits in the interpretive centre, the Lower Trails begin just outside the main entrance on the ground floor.

Head northeast on a distinct gravel pathway, passing the iconic tipi set against the endless blue skies and sea of grass.

In about 400 feet, keep left to head around the loop trail in a clockwise direction. The trail passes over an area of noticeably denser shrubs along a short boardwalk. A narrow channel here becomes a seasonal stream during rainstorms, and the increased water allows thirstier plants to thrive here, many of which are still collected by First Nations people (note: if that’s not you, please leave the plants alone!).

Just beyond the spring channel, the trail meanders close to the base of the cliff, which is one of the oldest and best-preserved kill sites in North America.

Beginning in 1938, archeologists digging here — with the help of local Blackfoot — were able to piece together the impressive timeline of this important kill site, which was used for this purpose since 3,000 to 5,000 years ago and through about the year 1800. By studying the types of tools and arrowheads left behind and the markings on the bones of the butchered buffalo, they began to get a better picture of what was happening here and when it was going on.

In this incredibly complex and complicated ritual, members of the hunting tribes would find V-shaped valleys leading toward cliffs like the one you’re standing beneath now (which were significantly taller those thousands of years ago, too!). Timing their hunts with the seasonal migration of the buffalo herds, people would build large stone and branch cairns along the plains to create visual boundaries and barriers to keep the buffalo herd traveling in one direction. In many cases, these lanes stretched for several miles and you can still find some of them standing amid the plains in this region.

Once a herd was located, people dressed in buffalo herds would infiltrate the herd and move toward the front of the group while others dressed as wolves would stalk along the perimeter of the herd, helping to direct it inside the cairn lanes.

A curious visitor inspects some of the wolf disguises inside the centre

Those who impersonated the animals had to study their movements for years before they could participate in the hunt like this. For the hunt to work, the animals had to believe they were being threatened by real wolves.

Once the setting was complete, the wolves would begin charging the herd, sparking panic. At the front of the herd, the people dressed as buffalo would take off toward the cliff. Once the herd was charging toward the edge of the cliff, the buffalo impersonators would have to jump outside of the cairn lanes at the last minute — or, in some cases, would hang onto the cliff itself while the buffalo jumped off, driven by panic and herd instinct.

Waiting below, fellow tribe members would kill any buffalo that survived the jump and move the carcasses to a butchering location nearby. Needless to say, this was sort of an all-hands-on-deck operation.

The trail continues beneath the cliff-side kill sites before looping back toward the tipi and the centre’s entrance. At about 0.7 mile, a spur trail heads southeast toward an overflow parking lot. It’s worth visiting this short offshoot instead of heading directly toward the trailhead, because you can walk past one of the few remaining tipi rings that have been found at Head-Smashed-In.

And even if you don’t, the views of the plains and prairies here are absolutely stunning.

Tags: alberta, canada, first nations, ford macleod, head smashed in buffalo jump, history, Native Americans, unesco world heritage site