One of Orange County’s most popular and accessible trails is also one of its most beautiful and diverse. The 3,789 acre Aliso and Woods Canyons Regional Park in Aliso Viejo features riparian woodlands, grassy meadows, rolling hills, views of the Santa Ana Mountains and Laguna Canyon, and sandstone caves all within a short drive from most of Orange County and northern San Diego County. This 11 mile loop is an all-day adventure that showcases the variety and beauty of the canyons.

The park protects a landscape that has a long history of human use. The Gabrieleño and Juaneño bands of Native-Americans co-existed on lands currently contained within the park, using Aliso Creek as the boundary between their lands. The region’s abundant wildlife, regular water sources, access to the ocean, large acorn masts, and built in shelters from nearby caves assured that both tribes would be able to live a rich and stable lifestyle. Like most of the Native-Americans in Southern California, both tribes were displaced by the Spanish, who “acquired” the land and re-dubbed it Rancho Niguel. The area maintained the name and line of ownership until 1960, when the land was purchased by three separate OC cities . The Mission Viejo Company purchased the land in 1979 and opened it as a public park in 1990, offering recreation opportunities to hikers, equestrians, and mountain bikers.

The region is also part of geologically significant rock formation with extensive oil reserves. Aliso/Wood Canyons represent the southern end of the Monterey formation, which stretches from Santa Maria and Kern County to about Mission Viejo. This formation is the source of Los Angeles’ and Southern California’s rich fossil fuel reserves. While the “easy oil” has mostly been extracted from this formation, the U.S. Energy Information Administration estimated in 2013 that the Monterey formation could yield about 13.7 billion barrels of recoverable oil through the use of hydraulic fracturing (better known as “fracking”). The catch, of course, is that the use of hydraulic fracturing in an area notorious for its seismic activity has been deemed a risky proposal at best, and it is unclear whether oil companies will be given the go-ahead despite the estimates that increasing oil production could generate 2.8 million jobs and generate $24.6 billion in state tax revenue. It should also be noted that a USC study considers those numbers to be gross over-estimations and therefore highly suspect. Furthermore, nobody has yet proven that fracking in the region will be economically viable, at least until gas prices reach a level that alter the ratio between production costs and profits.

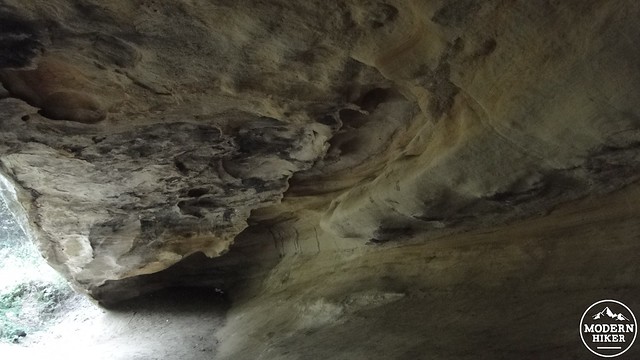

So, now that you have a better idea of what is sitting under Southern California, as well as a tiny glimpse of the possible battle that could brew should oil prices make hydraulic fracturing in Southern California economically viable, it’s time to talk about hiking. You won’t see any evidence of oil production at Aliso and Wood Canyons as most of the oil production in the L.A. metro area is centered in the Long Beach/West L.A. area. The other thing that is relevant about the Monterey formation is that, through the process of coastal upwelling, there are many pockets of sandstone with a rich marine history in various areas of the Laguna Hills region. This means that the easily eroded sandstone has formed a number of natural caves that have provided shelter to Native-Americans, outlaws, and weary hikers. Additionally, it may be possible to spot fossilized marine animals at various points on this hike if you keep your eyes peeled.

The trail starts out at a large parking lot on Awma Drive, just off of Alicia Parkway. After paying the $3 (at time of writing) day use fee at the kiosk (accepts cash and credit cards), place your receipt on your dash and get ready to hike. The beginning of the hike is, frankly, uninspiring, as it follows paved Awma and Aliso Canyon Roads for about 1.75 miles. This is mainly uninspiring since the views of the rolling hills and streamside vegetation intermingle with houses and other developed areas along the upper ridges of the canyon. Furthermore, asphalt hiking isn’t typically a joy. There is a sense that the real hike does not start until reaching the end of this stretch, as everything after it up until the return to this point is gorgeous.

At 1.75 miles, the road will reach a junction with the Woods Creek Trail, which is a well-maintained fire road branching off to the right. You’ll see a porta potty and a picnic table to the left, while Woods Creek tumbles along through a dense thicket of willow trees on the right. Follow the Woods Creek trail as it begins to travel up canyon with open oak woodland and meadows to the left and the willow-clogged creek to the right. This gentle and pleasant terrain will continue on for another .4 of a mile before coming to a junction with the Dripping Cave Trail branching off on the left.

Take the left turn and follow the Dripping Cave Trail through more oak woodland before crossing a usually dry creek. Another side trail will shoot off on the left and lead you over to the Dripping Cave itself. This cave was also once known as “Robber’s Cave,” as it once lent its shelter to a band of outlaws who used the cave as a “home base” from which to rob the stagecoach line passing between Los Angeles and San Diego during the 1800’s. The invention of I-5 made stagecoach robbery obsolete, although presumably the robbers were caught long before the internal combustion engine became king. Prior to los banditos, Dripping Cave also sheltered Native American hunters from foul weather during their pursuit of game. Even though this is fairly early on in the hike, the caves are a nice place to stop and rest for a snack. It also presents a decent place to turn back if you’re looking for a short hike. If you turn back here and retrace your steps, you’re looking at a 4.5 mile out-and-back trip.

For those who wish to keep going, backtrack on the trail to the cave and turn left onto the continuation of the Dripping Cave Trail. The next leg of the journey will take you up and over a scrub-covered ridge and then back down through a ravine with some nice sandstone features before dropping you off in oak woodland near a junction with the Mathis Canyon Trail. This segment offers some nice wildflowers during the spring season, particularly when the sage, monkeyflower, wild cucumber, ceanothus, and chamise in the scrubby areas are in bloom. You can’t reach the sandstone features from where you are, as the terrain gets a bit rough, but they provide a nice change in the scenery.

Turn left on the Mathis Canyon Trail and prepare for the main climb for this hike. There is an optional detour to the left to follow the Oak Grove Trail. This is not an essential detour, and I originally took it simply because walking under oak trees is a pleasant thing to do. If you would rather spend some time with the oaks and postpone the rough climb ahead, branch off on the left until reaching another bench, which will also allow a nice spot to take a break and eat a snack. However, there are more than enough oaks in Woods Canyon, and if you prefer to get the climb over with, stay on Mathis Canyon Trail and start trudging.

The Mathis Canyon Trail is a steep, uphill slog that is also pretty popular with mountain bikers. If you’re here on a Saturday or Sunday, there’s a good chance that you will spend at least part of this trail stepping out of a mountain biker’s way (that’s in direct contradiction to stated trail etiquette, which dictates that mountain bikers yield to horses AND hikers. Anyway.). On a sunny, summer day, this will be a long, tough climb, and it’s best to have some water handy, as there will be none along this stretch of trail.

Your effort will be rewarded once you join the West Ridge Trail, which runs along the southern ridge of Laguna Canyon. Once upon the West Ridge Trail, you’ll enjoy (marine layer willing) views north over Laguna Canyon and Crystal Cove State Park. Coastal views might be available, although I didn’t see them on this trip due to the marine layer. Once on West Ridge, you will follow the trail through its gentle undulations, past the Rock It Trail (very popular with mountain bikers) until coming to a junction with the Lynx Trail on the right. The Lynx Trail will serve as a scrubby, rocky connector trail to Woods Canyon, which, along with Dripping Cave, is the other highlight of this hike. This is the primary descent on the hike, and after this segment, the trail will be much gentler and smoother.

At the junction with Woods Canyon Trail, you will step into a cool, green corridor of oaks and sycamores alongside a perennial creek. This gorgeous stretch initially starts out on fire road, but I highly recommend joining the parallel single-track trail that runs along the north side of the creek. This single-track is not only officially closed to mountain bikers, but it runs through dense thickets of trees while the creek remains in view a large chunk of the time. You will want to be able to recognize poison oak, as there is an abundance of it growing here. I’ve included a photo, but it also helps to know that poison oak usually grows in cool, shady spots, often under oak trees. If you see clusters of leaves in threes growing in the shade, you are better off not touching it unless you love itching and scratching.

The parallel trail will eventually become the Coyote Run Trail, which passes through beautiful groves of oaks alternating with open, grassy meadows. This is a really beautiful stretch of trail, and it’s one of the areas in the park where the evidence of human development is not in evidence. Coyote Run will dead-end at a lower section of the Mathis Canyon Trail, which you missed when you joined it further up hill. Take a left onto Mathis Canyon Trail, cross Woods Creek at a concrete ford, and re-join the Woods Canyon Trail/fire road.

From here, it is a simple matter of following Woods Canyon Trail back to where it junctions with the Aliso Canyon Trail. Along the way, you’ll pass through a large meadow on the left which is plastered in mustard plants during late spring. The trail will cross the creek again on another concrete ford before continuing its gentle run through the corridor between oak woodlands and willow-choked Woods Creek. After reaching the junction, turn left onto Aliso Canyon Trail and follow the road back to the trailhead.As you near the parking lot, there is a nice native-plant garden off on the right that has signs describing what a variety of plants are. This is a good opportunity to not only get away from the asphalt, but to spend some time learning about the native plants in the area, in addition to their uses. You can cut through this garden to reach the parking lot, at which point you are back at your car and ready for a well-earned meal.

Tags: Aliso and Woods Canyon Regional Park, Aliso Canyon, Dripping Cave, Lynx Trail, wildflowers, Wood Canyon