The hike to Henninger Flats is a relatively moderate, non-technical climb up single-track trail and historic fire roads that is popular with hikers, equestrians, and mountain bikers alike — and for good reason. This route is in the front range of the San Gabriel Mountains, close to Altadena and Pasadena. It’s near the popular Eaton Canyon Falls (and the excellent nature center at Eaton Canyon), and is also one of the closest developed campgrounds to the Los Angeles region. With colorful history, a visitor center at the end of the trail, and unique campground views overlooking the Los Angeles basin, Henninger Flats is most definitely a trail that every hiker in L.A. should tackle at least once.

This route starts out from the Eaton Canyon Nature Center, where there is a fee to park (and limits on parking time — 9AM to 5PM). However, you can also park on Altadena Drive outside the entrance to the Nature Center. A popular alternative trailhead for Henninger Flats and for Eaton Canyon Falls is north of the center, off Pinecrest Drive — but I prefer the route from Eaton Canyon because the distance is about the same, and the route as described here spends less time on the Mount Wilson Toll Road in more interesting terrain.

Henninger Flats looms above Eaton Canyon

From the parking area in Eaton Canyon, you’ll be able to spot Henninger Flats almost immediately, far above the wide basin. Look for a stretch of unusually dense forest — much lower than you’d expect to see pine trees. That’s your destination.

Begin by following the trail toward Eaton Canyon Falls. Keep a left at 0.4 mile, and at 0.6 mile, take a right to turn onto the Walnut Canyon Trail.

If there were any crowds on the lower portion of the trail, you’re likely to leave them behind here.

The Walnut Canyon Trail is a short, narrow trail that climbs up toward the Old Mount Wilson Toll Road in a series of tight switchbacks through dense sage scrub. As the trail gains elevation, you’ll get better views of the front range of the San Gabriel Mountains as well as some nice perspectives on just how wide the drainage basin is for Eaton Canyon.

looking west toward the Verdugos

After climbing 637 feet, you’ll reach the Old Mount Wilson Toll Road just before the 1.2 mile mark after a tight switchback.

A mountain biker makes their way up the Old Mount Wilson Toll Road

In case you were wondering, yes, the Old Mount Wilson Toll Road is exactly what it sounds like — an old toll road to Mount Wilson. From 1891 to 1936, horse and carriage riders (and later, early automobiles) could climb up to the top of Mount Wilson from Altadena. In 1889, the construction of the Mount Wilson Observatory caused a bit of a Toll Road Race in the San Gabriels — knowing that the observatory would need an easy way to get supplies both during and after construction (and that students, scientists, and tourists would want access, too), several companies competed to cut their own pathways through the unstable San Gabriel front country.

Eventually, the Mount Wilson Toll Road Company won the bids and bought up the necessary land. A modest four-foot wide road was completed in only five months (!) in 1891, and a month later the toll houses were built with rates fixed by the L.A. County Commissioners. Hikers paid 25 cents while horseback riders were charged 50 cents (roughly equivalent to $7 and $14, respectively). The route was called The New Mount Wilson Trail and it was a great success, easily outpacing the traffic of the original route to Mount Wilson from Sierra Madre.

The Mount Wilson Toll Road in 1922.

The road was widened to six feet in 1893, and by 1905 the company built a wilderness resort to accommodate travelers who weren’t staying at other wayside camps like Strain’s or Martin’s Camps. Further expansions allowed more modern automobiles to travel the road, but when the Angeles Crest Highway reached Red Box and Mount Wilson in 1935, the Mount Wilson Toll Road Company closed their road and handed it over to the Angeles National Forest.

Today, it’s hikers and mountain bikers who make up the majority of the traffic on the Old Toll Road — followed by equestrians and the occasional firefighting vehicle. Gone are the wayside rest stops and inns, but hey, we still have some benches with nice views, so it’s not all bad.

It’s a straightforward hike from here on out — you’ll just follow the Old Toll Road as it meanders and climbs its way up into the San Gabriels and enjoy the views as they spread out around you (assuming a lack of haze or June Gloom). At 2.7 miles, you’ll pass the fourth bench and in another 0.1 mile you’ll see the entrance to Henninger Flats — as well as some mercifully flat ground.

the Toll Road climbs up, up, up

a mountain biker takes a breather near the Henninger Flats entrance

Coming up into Henninger Flats is an unusual experience. If you’ve spent time hiking in the San Gabriels, you know that most of the coniferous trees grow either on the north-facing slopes or at much higher elevations than this — but here is a lovely little campground shaded by towering pine trees in every direction. So, what gives?

This region began its modern history as a small mining operation settled by the Virginian William K. Henninger in 1880. Henninger married a Native American woman and raised three children while farming a modest fruit orchard here. In 1892, the Henningers were visited by Theodore Lukens, a former and future mayor of Pasadena and one of the earliest foresters in America. Lukens convinced Henninger to let him plant some conifers here as a reforestation experiment. William died shortly thereafter, and his daughters auctioned the land that eventually wound up in the hands of the Mount Wilson Toll Road Company and later the Forest Service.

Theodore P. Lukens

Lukens was able to take out a lease on this land from the Forest Service in 1903, where he founded the first experimental reforestation nursery in California.

Lukens — for whom the highest point in the city limits of Los Angeles is named — was known for traveling all over the forests of California, collecting seeds and pinecones to try to find tree species that would survive the region’s frequent wildfires. Considered one of the earliest modern conservationists, Lukens was one of the first people in the Los Angeles area to seriously look at the damage that mining, logging, and ranching were doing to Southern California’s landscape. He noted the increasingly powerful wildfires and the mudslides that usually followed them, and thought the hearty, fire-adapted knobcone pine would be well-suited to reforesting fire-denuded slopes in the San Gabriels. He organized the planting of several thousand knobcone and ponderosa pines in this region — some of which still stand today.

From the nursery at Henninger Flats, Lukens and his team grew more than 60,000 seedlings for the forests and parks of Southern California — including over 16,000 for planting in Griffith Park. John Muir even stopped by and was said to be impressed, but unfortunately the Forest Service had a differing opinion. Although Lukens was named Acting Supervisor of both the San Bernardino Forest Reserve and the San Gabriel Timberland Reserve (precursors to the San Bernardino and Angeles National Forests) in 1906, they also cut his firefighting force by more than half and declared the experiments at Henninger Flats a failure. The Forest Service at the time was less interested in finding fire-tolerant vegetation than they were in trying to make the San Gabriels a commercially viable source of lumber, which — let’s be honest — was never gonna happen, sorry. They were also frustrated that the trees weren’t growing as well as they wanted them to, mostly because trees like this aren’t really supposed to be growing in chaparral in the first place.

While Lukens was on vacation, the Chief Forester removed him from the Acting Supervisor position, and later that year Lukens resigned, tracked down John Muir in Yosemite and became actively involved with the Sierra Club, advocating for reforestation and watershed protection from ranchers in the San Gabriel Mountains. He also advocated for a park above the Devil’s Gate in Pasadena (now the Hahamonga Watershed Park). He died in 1918.

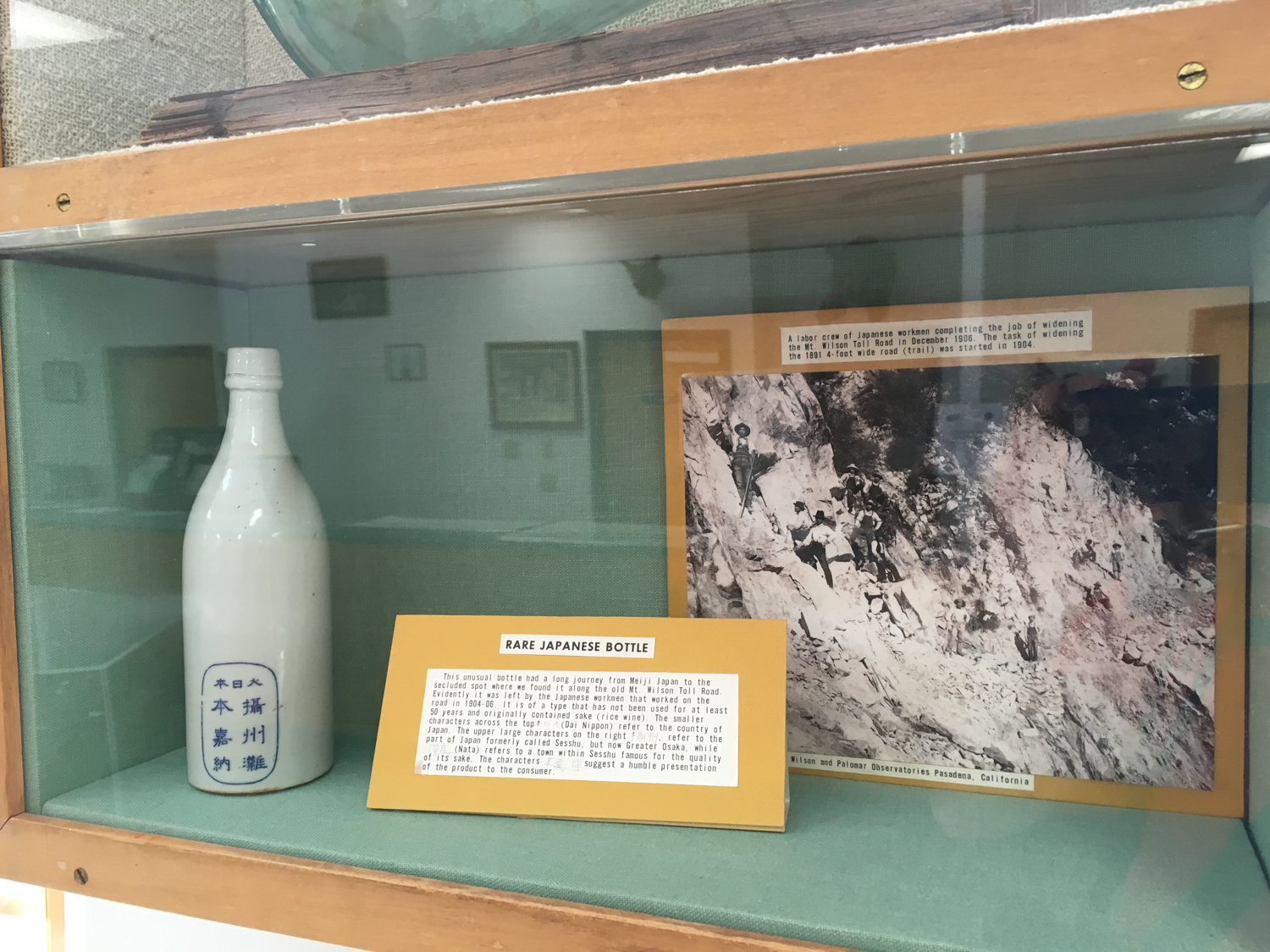

Those interested in more of this region’s rich and colorful history should pop into the Henninger Flats Museum, where a collection of artifacts and photographs bring this time period back to life.

This is one of my all-time favorite photos from the Great Hiking Era in the San Gabriels

In addition to the old photos and postcards, this museum also has one of the wheelsets from the O.M. & M. Railway (One Man and a Mule) that operated near Inspiration Point, as well as the original fire lookout tower that sat on Castro Peak in the Santa Monica Mountains.

However, the real show-stopper here are the spectacular views looking down on the cities below you. Whether you’re spending a night here at the campground or just stopping at a picnic table for a lunch before you make your way back down, you’ll appreciate these views (assuming the air is clear, of course), whether you’re checking them out during the daytime or watching the city lights turn on as the sun sets to the west.

When you’re done, return back the way you came.

Tags: Angeles National Forest, Camping, eaton canyon, forestry, henninger flats, history, los angeles county fire department, San Gabriel Mountains, theodore lukens