If you’ve ever wanted to learn more about the plants and animals around you but you didn’t have someone along for your hike or walk to ask, you’ll want to download iNaturalist. The free app is available for both iOS devices and Android devices.

In case you’ve attended one of my hiking presentations — or if you’ve read my wildflower guide — you know I’m already a big fan of this app and community. But maybe you’ve been a little intimidated by the interface. Or perhaps you’re worried you need to know some scientific terms before you get going. Well, I’m here to tell you to stop worrying and start observing with iNaturalist instead.

Why Should I Learn How To Use iNaturalist?

You enjoy hiking. You like being outside. Maybe you dig seeing a hawk flying overhead or spotting a field of blooming poppies while you’re outdoors, too. Isn’t that enough?

Well, yeah! Sure it is! As long as you’re following the park rules and staying safe and responsible outside, you should definitely hike the hike you want to have. But I can tell you from experience that learning how to use iNaturalist on my hikes has greatly increased my enjoyment and appreciation of every single hike I’ve taken. Where I used to just see steep slopes covered in shrubs, I now see individuals. Black sage next to a California sagebrush. Monkey flower sprouts emerging from nearly impossible cliffsides. A toyon providing shade near some showy bush sunflowers. And while I have taken some classes at native plant nurseries and read some books on the subject, the best learning always comes in the field.

iNaturalist can be used to record observations of all sorts of things — plants, animals, and even fungi. And you can even make observations in your backyard or on the street walking in your neighborhood. Helpful if, say, hiking trails are closed because of a global pandemic, for example.

How to Get Started with iNaturalist

Once you download the app or sign up on the website, you’ll create an account. At this time, you can issue a blanket license for your observations to let scientists use the data. If you’re more of a privacy-minded type, you can also change permissions of individual observations you make, too. (And you may want to be aware that a big part of the usefulness of this community is location and timestamp metadata, if you’re concerned about that stuff).

After that, you’re ready to start observing!

The easiest way to do this is with one of the smartphone apps. Just click OBSERVE at the bottom and your phone will snap a photo of whatever you’re looking at. And yes — animal tracks and scat both count, too.

After that, you’ll head to the details screen, where you can check the time and date and edit the privacy if you’d like. You can also mark whether or not whatever you’re observing is captive or cultivated (those are still useful to scientists!) and add to a project. Hit save — the iNaturalist app won’t upload until you tell it to, so you can wait until you get home to WiFi.

A note to those making observations on long hikes: check your settings! You can conserve a great deal of battery life by turning off things like WiFi, Bluetooth, and cellular data. You can also just use your phone’s camera app and then add those images to the app later. It keeps things simpler and it’s usually what I do. Also, don’t put your phone in full airplane mode — you won’t get geolocation data that way, and adding that information later can be a bit of a pain.

Check Your Observations

When you’re making your observations, iNaturalist will make an educated guess as to what you’re looking at. Provided you have a good picture, the system does a decent job of at least setting you on the right path based on the location of the observation, what time of year it is, and what other folks have seen nearby.

After you upload your observations and photos, others in the iNaturalist community will take a stab at identifying. You can watch and participate in the discussion and suggestions as they happen. Over time, I’ve used some of these back-and-forths to help me notice small differences in species that look similar. It’s also helped me start to remember some of those Latin scientific names for plants, too.

How to use Explore and Projects in iNaturalist

Ever wonder what else is hanging out in your neighborhood that you didn’t know about? If you hit the Explore tab on the app or on the website, you can set a map or search for a location to see all of the observations made in that area. If you’re getting good at spotting certain species, you can dive in and help others identify their observations. Or you could just poke around to see what else is around and keep an eye out the next time you’re outside.

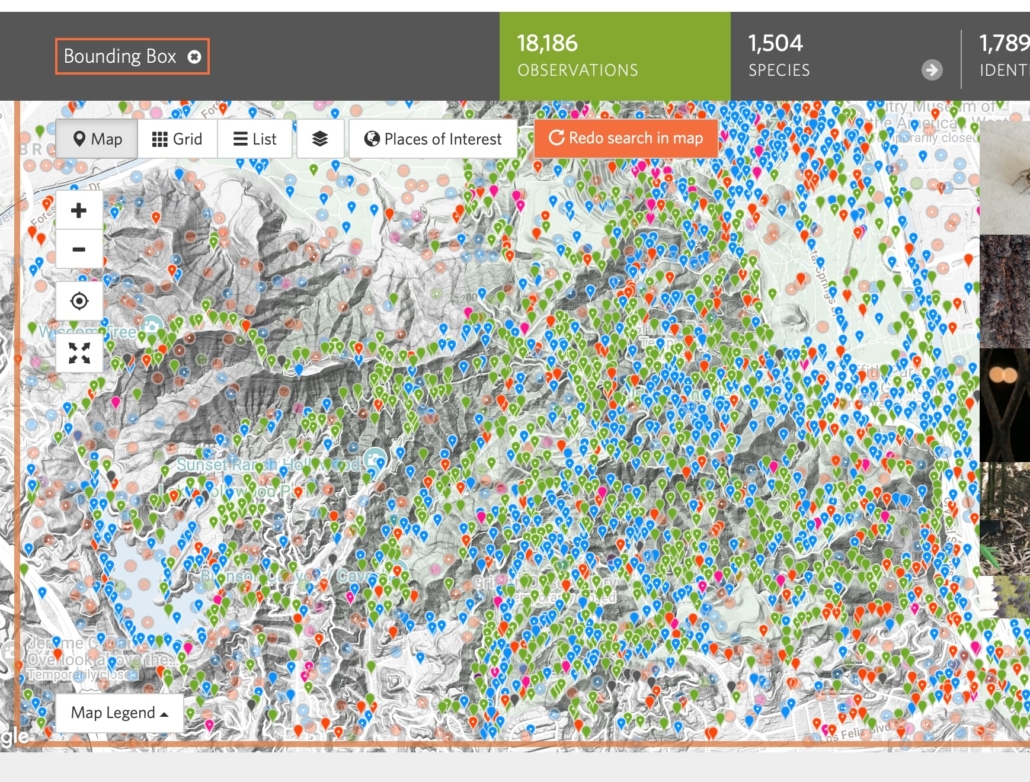

the iNaturalist project map for Griffith Park

You can also start following other observers and join up with or create your own Project. You might find a project based on a specific park, like this Griffith Park Biodiversity Project. Or you can check out a project devoted to a certain type of observation, like Fungi of the California Floristic Province. This is also where you can join up with timed events like the annual City Nature Challenge. Once you’re a member of a Project, you can add your own relevant observations to that group on the website or app (I find the site a bit easier for stuff like this).

And That’s It!

Now you’re well on your way to becoming a better naturalist and you’re helping with community science while you’re doing it. Now get out there and start observing!

- Download the iNaturalist app (iOS and Android) or sign up on the iNaturalist website

- Check your privacy settings

- Take some photos!

- If you’re in the field, conserve battery life by turning off cellular data, wifi, and Bluetooth but don’t go on full airplane mode or you’ll lose the geotagging

- Upload your observations

- Join some Projects and try to identify other people’s observations, too!

Tags: citizen science, city nature challenge, community science, inaturalist, observation