If you are planning on going to Maui, or if you’ve ever been to Maui, chances are that you have a certain set of expectations about what your time there will be like. The Valley Isle is famous for its climate, perfect beaches, snorkeling, laid-back style of life, winding highways to sacred pools, and the kind of good living that your credit card will not thank you for afterward. Somewhere way down at the very bottom of that list is the possibility for world-class hiking in one of the most unexpected and revelatory environments in the United States- the bottom of a dormant, 10,000′ high volcano.

Sure, if you’ve thought about Maui, you’ve probably also thought about the famous sunrises from the Haleakala visitor center (the sunsets are equally brilliant, by the way). After the beaches and the Road to Hana, the Haleakala sunrise experience is probably at the top of many peoples’ laundry list of activities for their Hawaiian getaways. But here’s what happens on a Haleakala sunrise experience: you get up at 3:00 A.M., drive your car or sit in a tour bus for several hours, sit in the freezing cold (yes, even in the tropics, the early morning is cold at 10,000′), watch the sunrise, then turn around and go back to the hotel.

The endeavor is definitely worth it if you have the good fortune of coming on a good sunrise day, but this is not guaranteed – the beauty of a sunrise here is entirely dependent on the clouds, which are not always present. If you come on a bad sunrise day, well – let’s just hope everybody you brought with you is a good sport about the 3 A.M. wake-up.

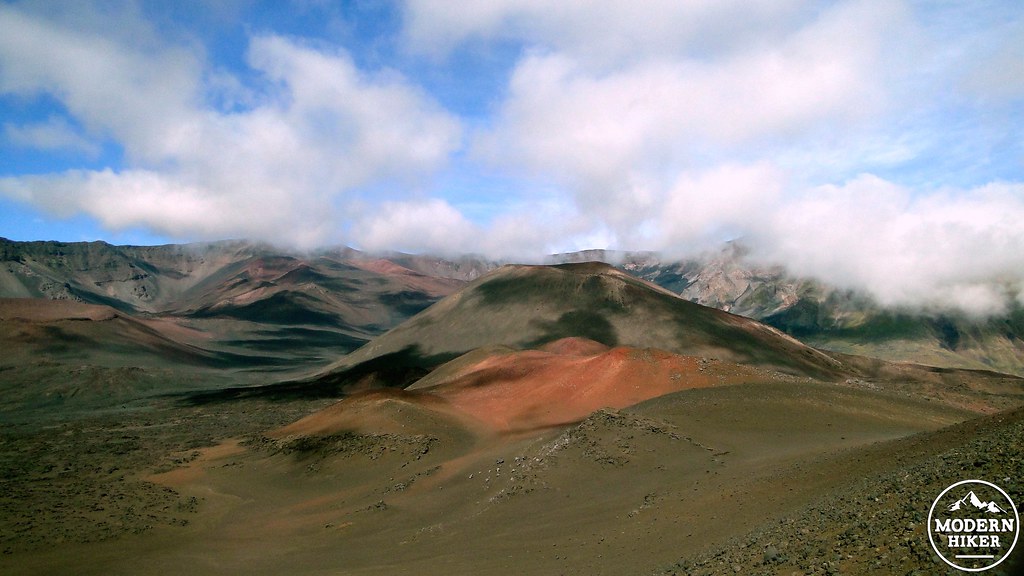

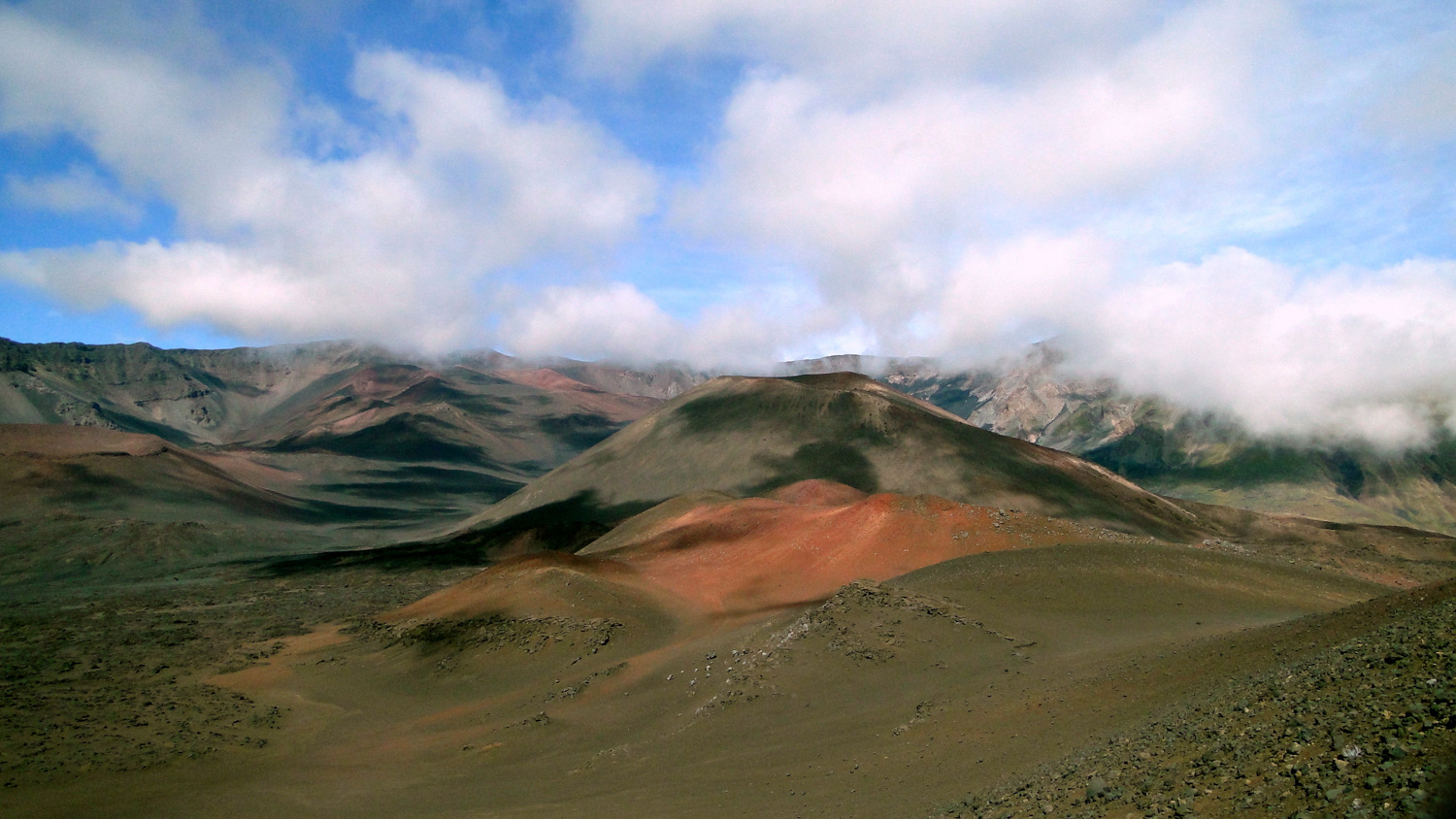

We are here to tell you that it doesn’t have to be this way. The sunrise at Haleakala is the opening salvo on one of the most incredible day hikes that I have had the privilege to take. If you set aside the entirety of the day to hike across the eastern third of Haleakala Crater, which is itself about the size of the island of Manhattan, I guarantee that you will raise your sunrise enjoyment exponentially on one of the most spectacular day hikes in the United States of America. You will cross a desert landscape that would look like it was lifted directly out of Mordor if not for the endemic Silversword – a distant relative of the yucca which produces a memorable bloom – and the equally rare flightless goose known as the Nene. You will circle cinder cones, walk across lava flows full of razor sharp rocks, pass and possibly camp in a cabin, all while watching the ever-changing cloud cover rolling into and out of the crater on the northeast trade winds.

Of course, that guarantee comes with certain qualifiers. This is not an easy hike as it takes place entirely above 6,990′ in a desert environment. The end of the hike involves a steep climb, and the temperatures can swing 30 degrees at a moment’s notice while rain and even ice can occur at practically any time. There is no water and no shade present on any stretch of the trail, and the physical environment is inhospitable with its myriad sharp edges. Given the length and elevation gain involved, this hike is recommended for more seasoned and physically fit hikers. However, any person of any ability can walk a brief portion of the Sliding Sands Trail just to get the feeling of being below the rim of the crater on brilliant red volcanic sand.

Haleakala, and the island of Maui that it dominates, owes its existence to its position atop a “hot spot” – a weak spot in the Earth’s crust that allows magma to rise to the surface of the Ocean floor – in the center of the Pacific Ocean. This hot spot is responsible for producing all of the Hawaiian islands. If one were to start from the Big Island of Hawaii and trace the 1,500 mile-long Hawaiian archipelago toward the tip of the Aleutian Island archipelago, one would be able to trace the line of movement of the Pacific Plate northwest over this hot spot for an estimated 32 million years. The Big Island, which is also the location of the most active volcanism in the chain, currently sits over the hot spot. Maui is the next island to the northwest, and it is therefore the second youngest in the chain. While it is unlikely that currently-dormant Haleakala will erupt below your feet, geologists do estimate that the volcano last erupted some time in the 17th century.

In addition to the geology of the place, the mountain’s dry, still air produces exceptional visibility. A large scientific campus not far from the Visitor Center takes advantage of ideal conditions to conduct astrophysical research. The United State Air Force, Smithsonian, Department of Defense, Federal Aviation Administration, and University of Hawaii all conduct research here, and the space-age looking complex – while off-limits – adds an extra layer of character to the summit. For your hiking purposes, the exceptional stillness of the air coupled with the lack of animal life caused by a near total lack of vegetation in parts of the crater will mean that you may experience silence at a level that you have never experienced and will possibly never experience again in your lifetime.

Finally, this hike is a shuttle hike that involves either leaving one car at each trailhead or hitchhiking from the Halemau’u trailhead back to the starting point. This is one of the rare locations where I have felt comfortable hitchhiking, as the vast majority of people traveling to the summit are tourists coming to see the sights. If you don’t feel comfortable with the hitchhiking option as many people will not, a shuttle option is an ideal solution. A less ideal solution is a walk of several long, uphill miles along the shoulder of Haleakala Highway, which will be less than appealing after the splendor of the crater.

This route begins at the Sliding Sands Trailhead, which lies at the southwest corner of the visitor center parking lot. After watching what could possibly be the most spectacular sunrise of you life, pick up the trail and follow it due south for a little over a hundred yards before bending southeast to make a long, gentle descent into the crater over brilliant red sands. If you’re only looking for a taste of the Sliding Sands Trail, it’s probably wise not to go too much further than half a mile. This hike starts at 9,775′, and given that you will have almost no time to acclimate prior to starting, an extensive return climb could cause altitude sickness. If you go much further, you are basically committing yourself to finishing this route or taking a long, difficult climb back to the summit.

Presuming you’re going all the way, continue along the Sliding Sands Trail as it meanders to the east. All around you now, the nearly barren walls of the crater soar high above. Closer afoot, solitary silver plants closely resembling yuccas shoot spectacular bloom stalks into the air as nearly the only vegetation around. This is the silversword, and it is an endangered endemic that you should keep well away from to avoid inadvertently damaging it. Aside from the crunch of your feet on the coarse volcanic sand, the only sound you will hear is a silence so profound that the rushing of blood in your veins can seem almost deafening. This is especially true in the early morning hours before helicopter tours begin buzzing the crater.

At 1.9 miles, a side trail branches off to Kalu’uoka’o’o (altogether, now!) cinder cone. This 1 mile diversion brings you to the brink of one of a handful of cinder cones dotting the floor of the caldera. These cinder cones mark recent eruptions, and they are essentially craters within the crater. If you visit the cinder cone, use caution around the edge as the last thing you’ll want is to slide down to the bottom. It’s not hot down there, but it would be very hard to climb back out.

Continuing past this diversion, the Sliding Sands Trail continues its way generally downhill and east past two more cinder cones and through fields of jagged lava rock. If you’re the superstitious sort, know that the Hawaiian fire goddess Pele is particularly vindictive to those who remove rock. For the more skeptical, know that the National Park Service can be equally vindictive to rock thieves. At 3.8 miles, you’ll reach a junction with an unnamed trail, at which point you will turn left to begin heading northeast.

The terrain becomes more jagged and rugged, and it’s wise to keep to the trail through here as volcanic rock is unmerciful in its ability to mangle footwear. After passing through these lava flows for .6 mile, the trail will begin to rise as it enters a field of smoother, redder volcanic soil approaching the base of Ka Pa Pua’a O Pele cinder cone. At 5.1 miles, the trail will make a sharp left turn northwest to trace the north side of the cinder cone. Continue past the junction branching off to the right as you merge onto the Halemau’u trail at 5.4 miles. From here, the Halemau’u Trail begins traversing another jagged field of lava flows northwest toward Holua Cabin.

During this traverse, you will slowly lose altitude to the point where you start to encounter vegetation. The vegetation is a curious mixture of tropical species growing in an alpine environment. You’ll encounter a lot of small ferns and shrubs, but nothing that grows particularly large. The vegetation is a welcome change from the endless black wastelands you just traversed, and since you are approaching Ko’olau Gap on the crater’s north side, it’s likely that cloud cover will start streaming up from the Hana Coast on the backs of the famous Hawaiian trade winds.

At 7.3 miles, the Halemau’u Trail reaches a solitary cabin situated at a grassy flat near the base of the crater’s western walls. This is Holua Cabin, which is one of a handful of cabins scattered across the floor of the crater. It is possible to stay at the cabin, although it is difficult to get a reservation due to the cabin’s popularity. If you wish to stay at this cabin for an overnight backpacking trip, you can find information on amenities as well as how to reserve the cabin in advance on the Recreation.gov website for Haleakala cabin permits.

After eating lunch at the cabin’s picnic bench or sleeping within the cabin’s confines, you’ll resume your now northward track on the Halemau’u Trail as it approaches the northwestern wall of Haleakala Crater. At 8.4 miles, the trail begins a precipitous switchbacking climb until gaining a ridge at 10.3 miles. Views back over the crater improve with every step, and the vegetation continues to become lusher and more tropical as you climb. The good news about this climb is that it does not ascend to the same height as the starting point on the summit, as the trail will deposit you several miles north and 2,000 feet lower than the Visitor Center. The Halemau’u Trail straightens out once it reaches the ridge and travels west along a scrubby plain to terminate at the Halemau’u Trail. From here, you can close the loop via your pre-parked car or by hitching a ride back up to the Visitor Center.

Tags: Haleakala, Haleakala National Park, hawaii, Holua Cabin, Maui, Sliding Sands Trail, Sunrise, wildflowers