Featured image by The City Project.

Last weekend, I had the tremendous pleasure of attending a roundtable discussion in Sierra Madre featuring some of the most important and influential outdoor authors and historians in the Los Angeles region. The event was held by First Water Designs and was well-attended – by more that 300 people according to their estimates.

The event had an overwhelmingly positive atmosphere. Professionals and amateurs mingled in the hall of the Sierra Madre Congregational Church swapping stories and sharing their mutual enthusiasm on all sorts of topics, from hand-drawn cartography, old stagecoach roads and foraging skills, to the history of the San Gabriel Mountains and Los Angeles region.

standing room only for the assembled crowd

The oft-heard claim that L.A. “has no history” could be easily disproven here – even if you only spent ten minutes or so listening to the authors speak. John Robinson, author of several hiking guidebooks and several indispensable and comprehensive histories of Southern California remarked that even he “never realized how much history there was here in the San Gabriels”until he was inspired to dig deeper after hiking the mountain trails.

The event did take some audience questions via a moderator – and while most were light-hearted, the mood of the room took a definite turn when the panelists were asked their opinion about the newly-formed San Gabriel Mountains National Monument. The question hung in the air and the room fell noticeably quiet.

Christopher Nyerges, author of several guides on foraging, longtime wilderness skills teacher, and tireless promoter of the benefits of being in touch with nature, took the microphone and simply stated, “Obama doesn’t giveth. He taketh.”

There was no response in the room, either from the audience or the panel – although it was not apparent if that was because people disagreed or if they just didn’t know what he meant. Nyerges quickly added, “When you protect an area as a Monument, you’re saying it’s all set.” Implying that once an area had been named a National Monument that it somehow became lifeless and invalid for outdoor enjoyment, he said “I wouldn’t teach there.”

the assembled panel of authors

That was about as close to fringe theories as the panel got, but I was surprised with how many of the panel seemed either ill or under-informed on the issue – especially since these were people who had in most cases devoted decades of their lives to living and breathing the San Gabriel Mountains. Another author said she was for the initial plan when the Park Service was supposed to take over because she said the Park Service is a better steward of history than the Forest Service traditionally is. Now that the Forest Service was still in charge, she was opposed – even though the most sweeping plan for the proposed Monument / Recreation Area only had the Park Service as advisors to the Forest Service after a 10-year study found a “traditional” National Park unit wouldn’t be feasible.

Other panelists wondered aloud whether the Monument designation would help with the primary problem in the Forest – funding (local groups pledged $3 million in additional funds for the Monument on the day it was named), as if it would be preferable to just do nothing on either the land protection or fund raising front. Would existing businesses be allowed to stay? (Yes). Would the new monument swipe water rights from the Foothill Cities or interfere with private land ownership or municipal sanitation and power? (No, no, and no). Why didn’t anyone tell them about it? And why can’t they say what they’re doing? All of these questions had already been answered and yet here they were, being presented as Great Unknowns.

Throughout this section of the discussion all I could think was, “Why can’t we have an adult conversation about National Monuments“?

The following day, I co-led a fundraising hike to help secure Sturtevant Camp’s preservation in Santa Anita Canyon, and again the topic of the Monument came up at a small gathering at the Camp. Adams’ Pack Station‘s Deb Burgess, who has been paying close attention to the proceedings, had her own concerns about the designation. The Monument’s current border (which has not yet been completely surveyed and finalized, she noted) currently includes portions of the historic Camp but none of its main entry points through Chantry Flats or Santa Anita Canyon, which both hold historic significance of their own and experience much heavier use by the public. She said she had “no idea” how the designation would impact the Camp or the Pack Station, but that right now she was just assuming not much would change.

Burgess’ concerns are valid, and to me they represent the sort of discussion that needs to take place with the new Monument designation.

Part of the problem, I believe, is from the lack of comprehensive media coverage. I tried to cover the Monument proceedings as accurately and even-handedly as possible during the lead up to President Obama’s declaration, but there was a lot of information to sift through that made it challenging for me to get into coherent, digestible thoughts – let alone a newspaper reporter with a hard word-count limit. The public expects relevant information to be hand-delivered to them in an easy-to-understand format, but I don’t think such a format exists with this topic – and maybe it actually can’t exist right now.

It is confusing that the Monument as it currently exists is only one of at least six different proposals for the region in either National Monument or National Recreation Area form, and the only form that didn’t have to go through Congress to come into existence (and really, Congress hasn’t passed much of anything since 2006 – several bills to create National Monuments in areas with near-universal public support have been gathering dust for a decade or more). The current borders exist with an almost shocking disregard for what has been excluded – especially heavy-use and historic areas like Santa Anita Canyon, Echo Mountain, Mount Lowe, and the Arroyo Seco, but when a Monument is declared by the President invoking the Antiquities Act, the Executive branch is bound to include “the smallest area compatible with proper care and management of the objects to be protected.” (PDF of mostly-finalized borders)

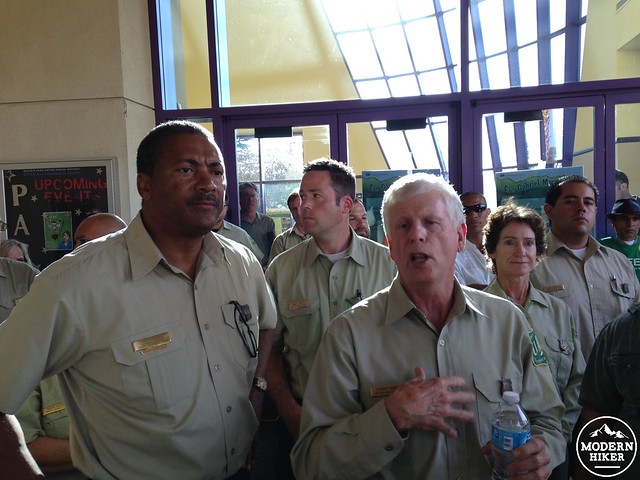

Chief Forester Tom Tidwell speaking to the public who were prevented from attending a meeting on the Monument in August, 2014, due to building capacity

It also doesn’t help that the process of creating a National Monument seems to be one of the most complicated, Byzantine, and nonsensical processes that exist outside of a DMV office. No one can really answer any specifics about what the Monument would be until after the Monument is declared – which seems pretty backward to most people, but is intended to give Monuments an incredible degree of autonomy in their policy process.

I think it’s that lack of answers – or the ability to give an answer, really – that is most responsible for the rising backlash. Chris Kasten, a geographer, cartographer, and longtime manager of Sturtevant Camp who was also at the panel, seemed to be its lone positive voice on this topic. He noted that many National Parks in California began their existence as National Monuments when either under threat from development or when Congress was dragging their feet on the issue. Citing the lack of upfront information in the seemingly-backward Monument designation process, he observed that often when you don’t have the information you’re looking for, you jump to the worst possible conclusion. In the face of unknowns, he said, “you’re either an optimist – or you’re not.”

That’s how you get opponents like Glendora Councilwoman Judy Nelson, who said the Monument “bypasses … the will of the people” with an Executive Order (via a power given to the Executive by Congress), or Mount Baldy’s Ron Ellingson, who said, “they’re going to put up a gate at the bottom of the road and start charging people to come up here (to Mount Baldy),” or Tracy Sulkin, who protested at the designation ceremony by hula-hooping and saying “the environmentalists won’t stop until the mountains are off limits to humans.”

looking toward Mount Baldy from the Hawkins Ridge. Most of the visible landscape is now included in the San Gabriel Mountains National Monument

None of those are legitimate concerns – and as this process moves forward, we should make an effort to offer the relevant information to people who say these things – or if they persist, to ignore them. The Monument is not a federal land grab. It’s not a prestige project. It’s not an overstepping of the legislature or ignoring the will of the people. It doesn’t snatch land or water rights or ban off-roading or shooting where it’s currently allowed, nor does it institute new fees, new restrictions, or re-education camps in FEMA trailers so the United Nations can take over the world.

There remain, however, serious concerns – including the boundaries of the Monument, what’s being excluded, and how we’re going to secure a continued and stable source of funding to maintain and protect our beloved San Gabriels. As the Monument process moves forward and those specifics and details start coming to light, it will take effort from all of us to ensure our mountains are getting the care they deserve. We will need to pay attention and to seek out that information when it becomes available and not expect it to be delivered to us. We will need to use public comment periods and attend community meetings. And most of all, we will need to let our Congresspeople know that our National Parks, Monuments, and Forests deserve better than what we’ve been giving them.

In closing, I turn to the last paragraph of the chapter on the Angeles National Forest from John Robinson’s book The San Gabriels, published in 1991. Its message was important almost a quarter century ago and it remains so today.

As Angeles National Forest approaches its centennial year (1992), it looks forward to challenges undreamed of a century ago. The current issues facing the Forest – overuse, vandalism, increasing pressure for recreational development, fire prevention and control – are primarily the result of the Angeles lying too close to a major population center. What happens on the Angeles National Forest, whether it becomes a better place to visit and enjoy nature, or whether it degenerates into something akin to an urban jungle, remains to be seen. The people who use the Angeles are the ultimate guardians of nature’s handiwork.